Part II: Becoming a Culturally-Based Youth Mentorship Program (2010-2016)*

[Note: This article is the second of a two-part series. Part one appeared in the summer 2017 issue of PHE Journal. Volume 83, issue 2.]

The Rec and Read/Aboriginal Youth Mentorship Program for All Nations evolved out of a series of community-based research programs that sought to engage Indigenous youth as physical activity leaders at their high schools. Rec and Read builds on the strengths, talents, and energy of Indigenous youth. Offered as an after school program, Rec and Read provides a supportive, wholistic approach to children and youth physical activity, nutrition and education programming. Designed by and with Indigenous youth, Rec and Read/AYMP has applications for all young people living in diverse communities. In part I of this two part series, we described our relationships with the pedagogical and theoretical Indigenous frameworks that guided the initiation of the mentorship programs. In part two, we discuss how Indigenous cultural approaches were strengthened as we expanded the program with additional urban sites, and adapted the program for inclusion in northern communities. All the while, our own (inter)cultural connections with Indigenous worldviews deepened, as did our commitment to the young people in our programs.

The transition years: Strengthening the theory and principles of Rec and Read

As Rec and Read/AYMP grew, we soon found ourselves in the challenging position of expanding our programs from the urban context (where, depending on available funding, we ran as many as seven mentors sites in one year) to northern communities. We introduced diabetes prevention as a means to secure necessary resources for new programs through health research funding, and soon we were growing in ways that we had not anticipated. With increased programming, our mentorship team was expanded to include an urban mentorship coordinator, and we secured multi-year funding to develop the leadership and employment skills for the urban high school youth, with the goal of preparing them for summer employment with the City of Winnipeg. At the same time, opportunities arose to introduce a mentorship program in Kistiganwaacheeng First Nation, a remote isolated northern community that was home for one of the urban mentors and a community experiencing high rates of type 2 diabetes (Amed et al., 2010).

Diverse contexts called for clear articulation of a program’s guiding principles; as we hired adult staff as both university and community mentors and trained new high school students to become leaders in their schools, we continually refined the mentorship model. And we welcomed new leadership to our intercultural mentor team: Heather McRae and Sonya Schulzki, responsible for the urban programs, and Jon McGavock and Pinar Eskicioglu, diabetes-prevention researchers who introduced the programs in the north. Here are their stories.

Urban programs: (Heather’s story)

During my PhD journey exploring culturally relevant sport for Aboriginal youth (McRae, 2012), it quickly became apparent that the ability of a non-profit organization to deliver its activities in a way that reflects their vision, mission and values is directly linked to their financial, human resource, relationships and networks, infrastructure and process, and planning and development (Misener & Doherty, 2009). I knew that Joannie, Amy and the early Indigenous youth participants had created something special; both my personal sport experiences and doctoral research project emphasized the need for culturally affirming theoretical models for urban Indigenous youth. It was exciting and a bit surreal to be invited to work full-time as a program director with Rec and Read and I was determined to build our organizational capacity to maintain the integrity of the program and ensure its long term sustainability into the future.

One of my first major projects with Rec and Read was to lead Joannie and Amy through a strategic planning process. One August day, we retreated to the country and through a series of guided program management activities, we articulated a Mission and Vision (see table 1), and claimed our commitment to an Indigenous wholistic worldview:

Rec and Read is guided by Aboriginal cultural teachings and worldviews. These worldviews call attention to a circular wholistic understanding of the world and all of creation. This influence is evident in our relationship-based, communal approach to multi-age mentoring.

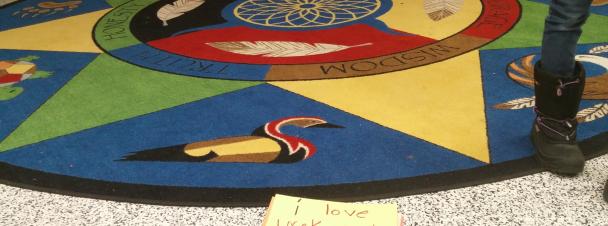

This understanding included insertion of the Medicine Wheel into our theoretical framework and cultural programming (see figure 4), always with the provision that different Indigenous peoples will have diverse interpretations of the Medicine Wheel teachings (Lane, Bopp, Bopp & Brown, 2003).

Table 1: The Rec and Read Mission and Vision Statement

Mission To develop and deliver relationship-based, communal mentor programs involving children, youth and adult allies from diverse cultural backgrounds.

Informed by Indigenous worldviews and practices, we seek to build on the strengths of youth from diverse populations to build healthy inclusive communities.

Vision Creating a world where all children and youth have safe healthy places to be, belong, grow and give of themselves.

Once we had a solid understanding of our program vision, mission and values, two key projects were introduced over the following year: revising and enhancing the program manual and creating a 20-hour staff training program. Over a series of weekly consultations with our university and community mentors, mentor coordinator Sonya and I refined the mentorship manual in ways designed to translate our Indigenous core values to practice. The Manitoba Education and Youth (2003) document, Integrating Aboriginal Perspectives into Curricula, guided our collective efforts to infuse and enhance Indigenous perspectives throughout our program activities. There are many different interpretations of the Medicine Wheel, and using Amy’s earlier work along with the provincial guidelines, we began with the “emotional” in the east as we worked through the four directions and what they meant within our programming (see Figure 4 for a sample from our curriculum workshops).

Figure 4: Staff Curriculum Mapping Activity Example (2013)

Over time, our theoretical model and interpretations of the Medicine Wheel have been shaped by the teachings of Elder Mary Courchene, Traditional Aboriginal Games instructor Blair Robillard, and the scholarly work of Kirkness and Barnhardt (1991) and Brendtro, Brokenleg and Van Bockern (2002). We understand the Medicine Wheel as a wholistic approach to wellness with specific teachings about living in a good way. To live in a good way, we honour the interconnectedness of all of creation and all dimensions of being – physical, emotional, mental and spiritual. The Medicine Wheel teaches us that all beings are connected, interdependent and work synergistically together to maintain balance within our communities and ourselves. Our communal mentoring approach reflects traditional Indigenous practices and worldviews. In a community, everyone has an important role to play. In the program, we recognize that the greatest teachers are often our early years participants; they too are “mentors” who help us rediscover our playful spirit, remind us of our responsibilities as role models and teach us humility, kindness and patience.

A highlight of those transition years was the weekend “culture camp” we organized in 2013. On a chilly October weekend, all of our urban adult mentors were invited to spend a weekend away on the land of Blair Robillard, our cultural games instructor who has been instrumental in the development of Rec and Read. For two days, we immersed ourselves in traditional Aboriginal games and activities, and the associated teachings, as taught by Blair, and grounded ourselves in the Indigenous ways that would guide our year’s forthcoming activities. We harvested dogwood, willow and other natural materials and learned how to make games equipment that we would later use in our mentor program activities.

In many ways, this weekend represented a turning point for Rec and Read, as we collectively immersed ourselves within a deeply meaningful cultural context that our adult staff fully embraced. As an intercultural community, we grew to be extremely proud of the Indigenous nature of our work, always careful to respectfully honor the local traditions, customs and protocols that we were taught. And with more and more non-Indigenous youth, including many newcomers, now participating in our urban programs, we have truly become, as Elder Mary Courchene advised in 2013, “the Aboriginal youth mentorship program for all nations”.

As a Métis woman working as the Program Director of Rec and Read and Community Indigenous scholar in my faculty, I have come to understand that the personal journey to reclaim my own Métis/Anishinaabe heritage is set within the context of larger cultural revitalization efforts in communities, schools and universities. I am thankful for the teachings of Elder Mary Courchene and Blair Robillard as well as cultural teacher Debra Diubaldo and Elder Carl Stone at the University of Manitoba. Their generosity, kindness, gentle teachings and wisdom have guided our efforts to create culturally affirming program practices, nurture culturally relevant educators, and to work and live in ways that honour the integrity of who we are and the world we wish to create.

Northern programs: (Jon and Pinar’s story)

(Jon) My entry point in the Rec and Read/AYMP story begins with a question: how can we support the need for physical activity among Indigenous youth living in remote communities who are at significant risk of type 2 diabetes? In 2007, I was invited to Kistinganwaacheeng First Nation by the local Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative worker, Larry Wood, to develop programs to address the high rates of type 2 diabetes in the community. Larry had surveyed the community regarding their needs for supporting persons with diabetes. The community overwhelmingly wanted resources for physical activity and for programs to focus on youth. Between 2007 and 2008, we secured a grant to build a fitness centre in the high school and piloted a series of initiatives. In 2008, I visited one of the urban mentor programs in Winnipeg’s inner city and was overwhelmed by the leadership and motivation the high school mentors brought to the program.

As I watched the children and youth mentors chase each other in a spirited round of tag in the gym, I wondered: could we replicate this enthusiasm in a program up north, where the cultural landscape was so different from urban Winnipeg? Additionally, could this program reduce risk factors for type 2 diabetes among Indigenous children in Northern Manitoba? When Joannie received a call from a Jessica Beardy, a young community member who had been a former Rec and Read mentor in Winnipeg, asking, “when are you going to start a mentor program in my community?” we immediately set a plan in action. Within a month, we sent a team of experienced urban mentors to visit the community. Over two days, we just spent time getting to know each other and talking about the program.

Nick Kojima, one of the university student mentors that joined us on the two-day visit agreed to spend three months living in the community to get to know the students and where they were at in terms of their interests and abilities. Taking the lessons learned from his 3 years working as a university mentor in the urban programs, Nick applied a strengths-based relationship building approach to getting the program started. This approach was different from earlier community-outreach efforts (e.g., the Northern Fly-In Sports Camps (Harper, 1992), as we allowed significant time for relationship-building and local capacity development. To be honest, I wasn’t sure how adaptable the urban program would be in a northern context, and somewhat to my surprise, it took all of one week for Nick to recruit a small team of high school mentors to visit the early years school at lunch and teach low-organized games on the playground. And just like that first group of four urban high school youth who walked over to Amy’s early years school five years prior, something special happened. Our northern youth became “mentors”.

Over the next 4 years, the program grew from 6 to 30 mentors and was being championed and delivered by one of the original high school mentors, Austen Flett. We assessed the impact of the program on risk factors for diabetes, showing that AYMP was effective for preventing weight gain and improving self efficacy among Indigenous children (Eskicioglu et al., 2014; Eskicioglu, 2015).

Six years later, with funding from CIHR (2012-2016), four additional rural communities joined the team, and a recent CIHR Pathways to Equity Team grant will bring us closer to the original vision of having mentor programs in every school in Manitoba and several in four other provinces in Canada. While we have focused our scientific efforts on measuring the mentorship program’s impact on the risk factors associated with diabetes, with promising results (see Eskicioglu et al., 2014; Eskicioglu, 2015), we have continually worked with teacher champions and youth mentors to help us understand how theory works. We quickly learned how each community has its own cultural orientations; our communities provide the cultural approaches within each program, and adapt the mentorship guiding principles according to their own sovereign traditions. In the next section, Pinar explains how we worked to understand theory better, once more turning to community-based participatory action approaches.

(Pinar) I started working with Jon during a fourth year fieldwork placement course before completing my undergraduate degree in Kinesiology. I was given the responsibility of assisting with the delivery of new mentorship programs in five communities, while also collecting data related to Jon’s research questions. I enjoyed going into the communities, which included Kistinganwaacheeng First Nation, Wabowden, Thompson, Sagkeeng and Sandy Bay, and meeting people, especially the youth mentors and grade 4 students. One of my first tasks in a new program was to share aspects of the mentorship model with the adult mentors and high school students. Using resources developed and shared by the urban Rec and Read mentorship team in the south, I would hand out mentor manuals to each of the high school mentors and community members. Together we would discuss the components of the Circle of Courage® and the Four R’s.

Our discussions were always led by the high school mentors who would share examples of how they interpreted the components and what each (e.g., belonging, mastery, independence, generosity; respect, relevance, responsibility and reciprocity) meant for them. From one community to the next, the mentors had different examples and ideas as they interpreted the theory into practice, including how they wanted to talk to the early years mentors about them. For example, one community drew an outline of the human body, and divided it into the four components of physical, emotional, mental and spiritual. Then early years mentors were asked to write words or draw pictures in each component about what that component meant for them. Another community had a bulletin board and students were asked to write down “what do you see, what do you hear, and what do you feel” in relation to each component of the Medicine Wheel. As we listened carefully to the early years and high school mentors from the north, we heard their voices echo those of the young people who first created Rec and Read/AYMP years ago. From the Four R’s, to the Circle of Courage®, through to our understanding of the four directions of the Medicine Wheel, our youth mentors continue to teach us as they breathe life into the theoretical constructs that guide our work.

The Future: Coming full circle to Mino’ Pimatisiwin

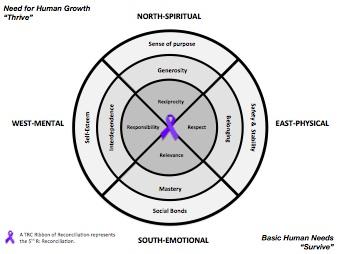

As we now engage in the rippling out of our mentorship programs across four provinces (Quebec, Ontario, Saskatchewan and Alberta), we again recognize the diverse and sovereign nature of the various Indigenous communities who will introduce new mentor programming. Within our urban Rec and Read programming, we find ourselves coming home to the core teachings shared with us by Anishinaabe Elder Mary Courchene in 2013. Speaking about Mino-Pimatisiwin, Mary has guided our current interpretation of the Rec and Read theoretical model, adding a richness that pulls together all the previous strands of theory (see figure 5). Mino-Pimatisiwin, also known as “the good life” (MFNERC, 2008; Hart, 2002) refers to the balance of our physical, emotional, mental and spiritual self that we all work toward; our development is guided by Medicine Wheel symbolism and teachings. As with the Circle of Courage®, our understanding of healthy development is informed by blending Indigenous and western ways, overlaying Medicine Wheel and circle teachings with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Figure 5: Current Rec and Read Theoretical Model (November 2015)

There are three overlapping circles within our current theoretical model. The inner circle represents the Four R’s: Respect, relevance, responsibility, and reciprocity by Kirkness and Barnhardt (1991), the middle circle represents the Circle of Courage®: belonging, mastery, independence/interdependence, and generosity by Brendtro et al. (2002), and the outer circle represents an adapted version of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Safety and stability, social bonds, self-esteem, and sense of purpose. Returning to the communal values of Indigenous peoples, we highlight that individual responsibility is an aspect of our larger interdependence. We use the example that in a community, everyone has responsibilities that are essential to the health and well-being of the larger community; the independent actions of our youth benefit the larger group in interdependent ways.

Our programs begin in the East – the physical – where we celebrate whenever high school and early years students simply “show up” and are physically present in the after school mentorship programs. Here, we emphasize respect as a means for everyone to achieve a sense of belongingness – a key component of safety and stability as understood through Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

In the south, we find ourselves in the direction of the social-emotional. With social bonds strengthened by a sense of belongingness, we are encouraged to develop our competencies in activities that are meaningful and relevant. For youth mentors, this can be leadership skills; for university and community mentors, this can be intercultural competencies; for our children participating in the program, this can be physical literacy or comfort in reading and playing games. We maintain our high expectations, noting that wherever our youth are at is where we focus our attention.

In the west, we have the mental component. Here, we encourage our youth to work together to make their program, community or society a better place for everyone to live. Empowered youth feel a greater sense of responsibility to their family, friends, school, and communities; we rely upon their contributions in ways that enhance self-esteem. By starting from where our youth are at, we try to understand the factors that influence their actions and decisions, always adapting our interactions accordingly.

In the north is the spiritual, encompassing the “core of our being”, who we are in the world and our sense of purpose. Blending generosity with reciprocity, we know that individuals and groups who recognize and utilize their personal and collective power in service of the greater good build strong communities. Youth feel important when they see how their actions benefit others and how our everyday behavior can make a positive contribution to another life. This is the core of what it means to be a Rec and Read/AYMP mentor; and we are proud to be grounded in Indigenous ways.

Returning once more to the teachings of Cree scholar Verna Kirkness, we have now placed Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s purple ribbon of reconciliation in the heart of our circle. This symbolism captures the contemporary reality of Indigenous-settler relations in Canada today and the need to build intercultural understanding throughout all aspects of our work. We are both excited and humbled by the opportunity to learn from the Elders who will guide all future programming.

Since the first pilot program in 2006, over 3000 mentors of all ages have taken part in over 70 mentor programs in the north and urban centres. Yet, sustainability remains a challenge when program funding is most often limited and health dollars are spent more on intervention than prevention. One solution we are exploring is to embed the after school programming within the school system, allowing students to gain a service-learning or leadership health and wellness credit for their participation. And if there is one lesson that applies to all contexts and/or obstacles: build respectful relationships. In a society working to overcome the devastating impacts of colonization, respect is key.

Conclusion

As an intercultural team dedicated to the reconciliation process, we are enriched by the Indigenous cultural worldviews and pedagogical theories that have informed our work. We are committed to be allies for the young people in culturally relevant programs, and are invested in the principles of Ownership, Control, Access and Possession® in our respect of the sovereignty of all First Peoples in our research. And, we have unfailing belief in the potential of Indigenous youth and all young people from diverse backgrounds to be “leaders of today” (Brendtro et al., 2002), foretelling the better tomorrows for all of us as we move forward on a pathway toward Indigenous cultural revitalization and reconciliation.

The authors are only a small part of the Rec and Read/AYMP story. They would like to acknowledge and thank the children and youth mentors, university and community mentors, teacher champions and all those who work in support of the programs. Thank you also to our funders, including SSHRC, CIHR, the Province of Manitoba and the University of Manitoba.