Part I: Initiating a theory-based after school physical activity program

[Note: This article is the first of a two-part series. Part two will appear in the Fall 2017 issue of PHE Journal. Volumen 83, issue 3.]

The Rec and Read/Aboriginal Youth Mentorship Program for All Nations is an innovative approach to after school programming that promotes Mino-Pimatisiwin, “the good life/living in a good way” (Hart, 2002), with a vision to reduce health and education inequities among Canadian youth. Applying a communal, relationship-based mentorship model (Carpenter & Halas, 2011), Rec and Read/AYMP invites high school students to work with university students and community mentors to develop and deliver a weekly after school physical activity, nutrition and education program for early years children. Over the past ten years, Rec and Read/AYMP has clearly illustrated that Indigenous youth and young people from diverse backgrounds want to be actively engaged as volunteer mentors in their schools and communities. Given its wholistic nature, Rec and Read/AYMP has been shown to positively attenuate risk factors for type 2 diabetes (Eskicioglu et al., 2014) while also addressing multiple social determinants of health.

The seeds of the mentorship programs were planted in 2004 when one Indigenous youth chose to respond to an invitation to participate in a participatory-action research project that investigated the quality and cultural relevance of physical education for Aboriginal youth (see Carpenter, Rothney, Mousseau, Forsyth & Halas, 2008). In a follow-up study, we added to our understanding of culturally relevant mentoring by embedding Indigenous teachings and worldviews as guiding principles for our activities (Carpenter, 2009). Over time and with input from the children and youth participants, Elders, community leaders and teacher champions, Rec and Read/AYMP has emerged as a culturally affirming after-school program that affects positive behavior change in relation to healthy eating and increased physical activity. Rec and Read also provides educational and employment opportunities and enhanced social networks for the youth mentors, many of whom live within low-income and/or racially marginalized contexts.

Perhaps what is most impressive about Rec and Read/AYMP is that it builds on the leadership skills of young people living in communities where social, economic and health inequities are greatest. These young people envision a society where mentor programs exist in every school and community, and this paper is a step toward fulfilling the dreams of the youth mentors. By sharing our stories about how the theoretical mentorship model has evolved over time, we hope to illustrate how the reclamation of Indigenous perspectives provides a pathway for health and physical educators dedicated to building intercultural bridges for youth. Embedded within the discussion of how theory has informed Rec and Read/AYMP, we each touch upon Shawn Wilson’s (2008) acknowledgement of the importance of the research and learning journey, where our relationships with our ideas evolve in personally and professionally meaningful, if not transformative, ways. As an intercultural team with a mix of Anishinaabe/Métis and non-Indigenous colonial settler heritage, we place great value on relationships, which are at the core of Rec and Read/AYMP’s success.

The first year: culturally relevant physical education

Joannie’s story: I began my academic career at the University of Manitoba with a concern about the absence of Indigenous post-secondary students who were pursuing physical education as an educational and career pathway. Having been a public school physical educator for ten years, I had taught many Indigenous youth from diverse cultural backgrounds and was often impressed by their enthusiastic participation in my classes. Not seeing any Indigenous students in my classrooms at the University of Manitoba raised red flags and as soon as I could, I launched a research project to help me understand what was happening. If I wanted to know why Indigenous youth were not choosing physical education as a university program, I would have to go to the source, the youth themselves.

In years one and two of a SSHRC-funded (2001-2004) research project, our research team interviewed more than 100 high school students about their experiences in physical education. We found that Indigenous youth wanted to be active, but experienced a number of significant barriers in accessing culturally relevant, supportive programs (Champagne & Halas, 2003; Halas, 2006, 2011; van Ingen & Halas, 2006). To address these issues, we adopted a participatory action research methodology in the third year of the project as a means to engage young people in determining their own pathway toward enhanced physical activity opportunities at their high school. Given how popular some sports were for my former students, I anticipated that we might co-create an after school competitive hockey, basketball or volleyball league designed specifically for Indigenous youth. Much to my surprise, a completely different program emerged.

We began the research by inviting young people at one urban high school to join me in developing a leadership program. When one young man responded to a call for participation over the school’s PA system and returned the next week with three friends, we were on our way. Supported by graduate student Amy Carpenter, the activities that we co-developed with the youth would eventually lead to the high school students teaching low-organized games to children at a neighbouring school where Amy taught grade 2. To guide our interactions with the youth, we adopted key principles of Gloria Ladson-Billings’ (1994; 1995) culturally relevant pedagogy: high expectations for student success, the need to affirm the cultural competency of students, and the need to infuse critical social consciousness into the learning experience. As a non-Indigenous researcher-practitioner, my own critical social consciousness regarding colonization and its impacts on Indigenous peoples was sorely inadequate and I felt most comfortable grounding my work in the anti-oppression, intercultural pathways offered through Ladson-Billings’ research and scholarship.

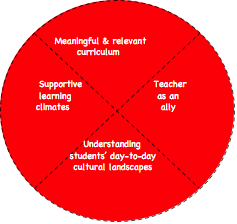

In those early months of working with the high school students, Amy and I translated the three principles of culturally relevant pedagogy through four inter-related concepts (see figure 1). These included “teacher as ally” where we shifted the power relations in our relationships with the four male youth mentors such that we saw ourselves as co-learners and focused our attention on what the youth would teach us. [1] We spent a lot of time just hanging out and getting to know the four young men. By priorizing relationship building, we had the time to develop a deeper appreciation for how the realities of the young men’s day-to-day “cultural landscapes” of inequity, racism, geographic dislocation, safety, security and financial instability/insecurity impacted how they experienced themselves within their school and community (see, e.g., Halas, 2006). We saw the youth as full of often-untapped strengths and built on those qualities as the high school students assumed their responsibility as role models for children, which happened almost by accident.

Figure 1: culturally relevant physical education

With after school gym time already booked for interschool sports at the high school, Amy offered one day to book the gym at her early years school for us to use. Her suggestion prompted me to ask the students whether they would like to see “what an introductory university class looks like?” The under-representation of Indigenous students in post-secondary physical education programs was always in the back of my mind, and I immediately envisioned teaching the young men not only games, but concepts about safety and inclusion, just the way we do in a first year games course. Amy added an important incentive: with her Grade 2 students relegated indoors all week due to a bitterly cold winter, she asked: “Will you come at lunch time one day to teach my students the games you learn?”

Over the next few weeks, we taught the young men different ways to create “supportive learning climates” that encourage active participation in the gym. Then, we invited them to take the lead in teaching games and activities that they found meaningful and relevant:

“In one of the introductory leadership activities, all of the mentors are asked to take turns teaching each other a favorite game or activity from their childhood. As the games are played, the mentors are encouraged to think about the types of students who might be reluctant, shy or less confident, and strategize how to maximize the active engagement of everyone involved” (Halas, McRae & Carpenter, 2012, p. 198-199).

When they felt ready, the four students walked over to the early years school at lunch, and with Amy’s support, led the children in a series of games. Soon, shrieks of excitement filled the air as the children and youth played low-organized games together. Interestingly, over the next few weeks, the high school youth started to visit Amy’s class during the school day, offering to help out. We were on to something worth developing.

As we reflected on how the program we co-developed first took shape, we saw the interconnectedness of the four components of culturally relevant physical education: in our adult mentor roles, we positioned ourselves as allies for the youth, working together to create supportive learning climates that acknowledged and affirmed the youths’ day to day cultural landscapes, such that they would purposefully engage in the physical activities we were planning and then delivering for younger children. The model was circular and resonated with the circle teachings of Indigenous peoples, where everything is seen as interconnected. All the while, we embedded our high expectations within efforts to affirm the young men’s cultural identities while developing, where we could, socially critical dialogue about their experiences in school and their community. As we began plans to replicate this emerging mentor model, we held close to Ladson-Billings’ (1995) guiding principles of culturally relevant pedagogy to inform our practice.

The formative years: Introducing the Circle of Courage® and the Four R’s

Amy’s story: Something magical happened that first year when the four students came to teach my Grade 2 students low-organized games: my students saw the young men as teachers and the emotional bonds that developed between the high school youth and early years children confirmed our initial observations that we were on to something. I had recently begun my Masters degree, and with support from Joannie and her colleagues Janice Forsyth and Michael Heine, we were able to build on our initial mentorship ideas as part of a larger SSHRC (2005-2008) grant that sought to develop a cultural approach to urban Aboriginal sport and recreation (Forsyth, Heine & Halas, 2007). Over the next two years, we worked with different groups of youth to pilot an after school mentorship program at one mentor site, then a second, each time working to identify the key components that made the program successful and relevant for both high school mentors and participating children.

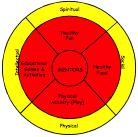

With an expanded mentorship team that included an Indigenous community member (Joseph Mousseau) and a university student in physical education (Alex Rothney), we collaboratively built upon the mentorship ideas from the previous year. This included the need for food (always a healthy snack), physical activity programming (a must for healthy living), and “reading,” which we interpreted as any activity or game that encouraged literacy, numeracy, and problem-solving, such as Connect Four, Jenga or reading a joke book with a big mentor. And we began to insert the Indigenous teaching practices that I was using in my work as a Métis educator, such as sharing circles and wholistic approaches to learning that seek balance across physical, social-emotional, intellectual and spiritual activities, thus “rec” and “read” (e.g., Carpenter, 2009).

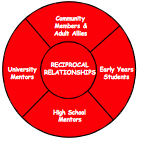

It was immediately evident that relationships were at the core of each activity: relationships between ourselves and the high school mentors; relationships between the high school students and the children who took part in the program; and relationships with our ideas. Relationships are a foundation of Indigenous epistemology and ways of being (Wilson, 2008), and as I strengthened my personal relationship with my own Métis heritage, I began to see more clearly the wholistic connections within the non-hierarchical, mentorship model we were developing. We adopted two key Indigenous approaches in our work: reciprocal multi-age mentoring (see figure 2) and wholistic programming that acknowledges the body, heart, mind and spirit (see figure 3). With a program framework identified, we turned to interpretive research methods to help identify other cultural aspects that were informing our work (Carpenter, 2009).

Figure 2: Reciprocal multi-age mentoring

Figure 3: A wholistic mentorship approach

As Joannie, Joe, Alex and I shared our favorite stories with each other from the first year of the mentorship programs, it quickly emerged that our interconnected work in the program closely aligned with Brendtro, Brokenleg and van Bockern’s (2002) Circle of Courage®. Purposeful reflection is often at the root of inspiration and we identified how the four components of the Circle of Courage®, belonging, mastery, independence and generosity, helped us build on the strengths, energy and talents of our youth and community. We set expectations high and the youth responded in kind.

Believing in the intelligence and talents of Aboriginal youth, we worked with the young people in our study to encourage them to be physicallyactive in their communities, to utilize their strengths to foster communitydevelopment and to empower each individual to recognize the strengths that he or she has to share (Carpenter et al, 2008., p. 57).

When we re-introduced the mentor programs the following year, we more clearly understood the relationship between the Circle of Courage® model and our activities. And then we used qualitative research methods of de-briefing circles, focus group and individual interviews to further enhance our understanding of how the youth experienced the programs they were developing and delivering, with our support. Through this process of interpretation, we came to see how the Four R’s (respect, relevance, responsibility and reciprocity) developed by Kirkness and Barnhardt, (1991) were an important complement to the Circle of Courage® (Carpenter & Halas, 2011).

How did we achieve a sense of belonging in the program? Through respect: for ourselves, each other, the children, our ideas and the program. How did we achieve mastery? By identifying activities that were relevant, again, for ourselves, each other, the children, and our aspirations in the program. How did we promote independence? By shifting responsibility for the program success to our youth mentors. And generosity? The program is founded on the reciprocity shared between all participants; by giving of ourselves in the mentorship program, in whatever responsibilities we assume each day, we are also receiving; we are uplifted by the smiles and joy on the faces of the children, we develop our own intercultural leadership skills, and we acquire new friendships that expand our social networks in tangible ways. As theory goes, our collective efforts to engage diverse groups of youth were becoming more deeply aligned with Indigenous ways and it was the high school mentors who helped us to see these connections more clearly (Carpenter & Halas, 2011). Throughout, we were a circle, not a hierarchy.

Importantly, very affirming social bonds began to emerge between the high school youth and the university students hired to support the mentorship programs. As mentor teams, the multi-age communal relationships crossed diverse cultural, class and ability backgrounds. As the research dollars trickled down to zero, Joannie piloted the delivery of a new three credit hour experiential learning course called Diverse Populations Mentorship. Here, university students participated in a guided practicum where they were placed at one of the mentor sites. Course evaluations were very positive, as were the experiences of the children and youth in the program; by year three, we were asked by the high school mentors and/or the schools to extend programming an extra month into spring. We obliged. We didn’t always have the resources to extend the programming, but we had keen participants and we somehow made things work, often through the extended volunteer efforts of our university students and teacher champions.

Challenges encountered along the way

The best way to overcome challenges that arise is to always to focus on strengths. Over the years, there have been days when few mentors show up for any number of reasons related to the challenges in their day to day lives; when this happens, we always focus our attention positively to celebrate those who are present and have made it to the program. When chaos emerges in the gym, as it sometimes does when young people are learning to be activity leaders, we go with the flow and provide encouragement and support. Sometimes, access to the gym or kitchen is restricted; in these cases, we creatively make use of open areas and order healthy snacks that are easy to prepare. When school personnel change over the summer months, we need to identify new teacher champions in the fall; thus, we try to build multiple relationships in schools and work to ensure we have effective communication with teachers and administrators. Given that program funding is often limited, securing multi-year support can be difficult. This is where theory becomes so important; when program practices are grounded in theory, participation outcomes are more likely to emerge in a consistent way across diverse groups, thus strengthening the case for funding.

Summary

Five years after that first winter day in 2004 when one young man responded to the invitation to help build an Aboriginal youth leadership program, approximately 100 children, dozens of high school youth, and ten university students had participated in the after school programs. A new university course supported its delivery, helping to build inter-cultural bridges and reciprocal learning between the high school and university mentors who co-developed and delivered the physical activity programming each week. While we began with the theory of culturally relevant pedagogy, it was when we infused two Indigenous theories, the Circle of Courage® and the Four R's within a Medicine Wheel format, that our key program principles became more clearly defined. As a theory-based after school physical activity program, we felt we were on to something good and wondered, what next?

In part II, we describe how the Rec and Read/AYMP mentorship programs were expanded from two to as many as seven urban Winnipeg mentor sites, and seven northern First Nations and Métis communities, with plans to expand to four provinces in the future. It’s a continuing story with a common theme: theory matters, culture matters more. Rec and Read/AYMP is evolving into a relationship-based, culturally-grounded mentorship program that benefits from the rich Indigenous culture and traditions of Manitoba’s First Nations and Métis peoples. And as individuals, we are also evolving, as Indigenous ways transform our personal and professional journeys.

Endnote

The authors are only a small part of the Rec and Read/AYMP story. They would like to acknowledge and thank the children and youth mentors, university and community mentors, teacher champions and all those who work in support of the programs. Thank you also to our funders, including SSHRC, the City of Winnipeg, Province of Manitoba, PHAC, Sport Manitoba, MHRC/Research Manitoba, CHRIM, CIHR, the Canadian Diabetes Association, the Winnipeg Foundation and the University of Manitoba (Faculty of Kinesiology and Recreation Management, Office of Indigenous Achievement, and Donor Relations).

[1] An ally is defined as a person in a position of privilege/power who uses his or her position to work in support of individuals in positions with less privilege/power.